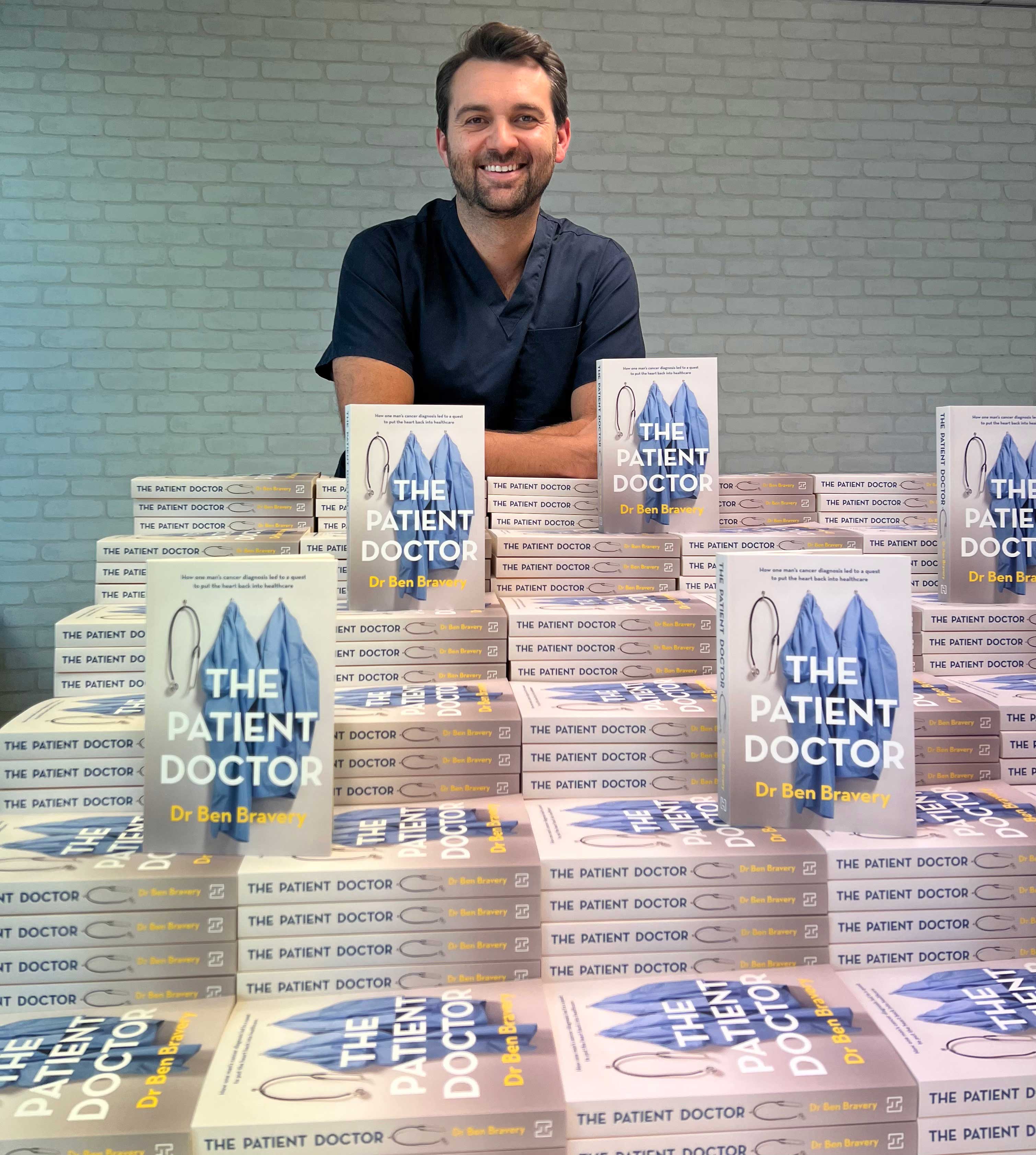

From the Science Circus to the ‘circus’ we call healthcare, Dr Ben Bravery (Bachelor of Science (Honours) ’03) has seen it all: the traumas, the tricks, the wonders, the schtick (and the animals). And now he’s written a book about it, The Patient Doctor. Oh, and by the way, he survived Stage 3 colorectal cancer at age 28 and completely changed life direction. Contact chats with Dr Bravery about his book and how his cancer diagnosis changed his life.

Q: You were obsessed with animals from a young age and studied zoology (not zoo-keeping!) straight after school. You then qualified in science communication, completed a medical degree, and are now training to be a psychiatrist. Do you see many similarities dealing with animals and humans?

A: I learned about the interconnectedness of life from my zoology training. To truly understand an animal, you need to study its environment, and I think that applies to humans too. However, because animals can’t talk to you, it’s all about the power of observation to collect information, whereas with humans, at least you can ask questions. I still observe facial expressions and body language for both though.

Q: You’ve written a book about your experiences as a cancer patient, how the immensity of the healthcare system can hinder rather than help, and how this spurred you to change careers. Do you think you made the right decision?

A: Yes, 100%. I decided to become a doctor while undergoing treatment as I thought it would be a good way to give back. I realised that one day I would die… I had a sense of my own mortality, and so I went to med school to learn why and what had happened to my body. I had also noticed that the health system makes it very hard to be flexible and is not always in the best interests of patients, and that to change healthcare I would have to enter it. I think I can make a difference. I still feel as motivated and passionate as I did when I knew I had another calling in life. I still maintain hope for medicine.

Q: There’s an old saying that you don’t have to have a baby to be an obstetrician, but do you think being a patient before becoming a doctor is helpful?

A: I don’t think it’s necessary for a doctor to be sick to understand sickness. We can show them what it’s like to be sick through sharing the lived experiences of others, and teach them empathy, compassion and how to listen. I think it definitely helps if patients and doctors better understand each other, because both depend on each other. If we are both on the same page, we get a better outcome. But differences between patients and doctors will always exist, which is why doctors must compensate for these by making sure their patients are heard.

Q: Are listening and politeness vastly underrated in the medical profession?

A: Yes. Doctors receive excellent training in medical knowledge and skills but, unlike other allied health professions, they are not rewarded for these ‘soft skills’ – and often have no time to implement them anyway.

Unfortunately, many doctors tend to develop a cynical outlook or get ‘compassion fatigue’ because their training and the intensity of the job changes them as a person.

Q: How can the healthcare system improve?

A: Healthcare remains system-centred. We need to change the focus to human-centred, not just patient-centred or doctor-centred. But this is easier said than done!

Q: Do you have any personal quick fixes that could help?

A: More staff. More beds. Better food and uninterrupted lunch breaks. Name badges for staff. Second ward rounds or – even better – thorough, unrushed ward rounds? Patients should always have someone supportive with them, where practical, and should get a notebook just for medical stuff – somewhere they can jot down questions between appointments and the names of doctors who look after them. Medical students learning directly from patients – this type of patient contact is known to help medical students develop skills, knowledge and empathy, and what students learn at medical school forms the basis of their knowledge for the rest of their careers. Cultivate empathy. Good teaching + good training + ample time = good doctor. We need to fix the system one patient and one doctor at a time.

Q: Your story is intensely personal – particularly when talking about the most basic of bodily functions – yet your honesty has made it accessible. And funny. Did having a sense of humour help get you through your medical treatment?

A: Yes, but humour only gets you so far. Eventually, you have to add other things such as spending time with family and friends, visiting the psychologist and exercise. Humour is good as part of coping but you must be patient too.

Q: Speaking of basic bodily functions, does this mean changing your son’s nappies is not a problem for you?

Actually, I’m better at changing nappies than my wife – she finds it gross!

Q: When writing a memoir, even though it’s about you, it’s also about the other people in your life. How did your family react to being portrayed in such a brutally honest way?

A: My family has been overwhelmingly supportive, but I did have to have some sensitive conversations about the material. Although it’s my story, it’s also partly theirs – but I’m telling it through my lens with my memories. I thought it was important to be open and reassure them that I love them, and no-one actually said ‘you can’t say that’ because they knew what I’d gone through.

Q: Are you looking forward to your future role as a ‘doctor of the mind’ and do you think you may end up teaching future doctors one day?

A: I feel great doing psychiatry: there’s more emphasis on the person – and having conversations – and it’s all about having an alliance, not a doctor/patient relationship. I like that psychiatrists don’t separate patients from their environment and don’t always rush patients: trust takes time. And, although psychiatry services are among the busiest and most stretched in our public hospital system, psychiatrists have held on to their holistic approach to illness. I’m really looking forward to it. And yes, I hope to be able to teach undergraduate students one day. I’m really excited about the opportunity to influence the attitudes of future doctors.

Q: One of your first jobs after graduating was performing in the Science Circus, which then set you up to move into science communication generally. Do you have any special tricks from those days you still use?

A: When I worked at the Science Circus, I learned to provide information in as many forms as possible. And what that means now is that when I’m speaking to a patient, I layer information. For example, if I’m trying to explain a diagnosis, the first layer might be to describe the condition in technical terms, the second layer would be to reduce those terms to plain language, and the third would be an analogy. That way, whoever else is listening can help communicate the message in a way they understand. Some doctors just drop the technical terms and then run, which is not always helpful.

Q: Finally, what advice would you give to anyone with niggling concerns about their health?

A: I think that any concern about your health is important because it’s come to your attention. It’s natural these days to go to Dr Google and I actually encourage this because you can get a lot of knowledge. But don’t stop there because you can end up in a dark place. Go to a doctor and discuss your concerns. That’s what I should have done; I may have had a completely different outcome had I not stopped at Dr Google – because real-life medical doctors not only have knowledge, they can apply and interpret it.