From droughts to raging bushfires to devastating floods, Australia has seen an alarming increase in the severity of weather events in recent years.

Despite this, many believe our nation’s political leaders have failed to take real action against the threat of climate change.

But why is this? And what role does science reporting play in this narrative?

Join award-winning journalists and UQ graduates Marian Wilkinson and Tegan Taylor, as they lift the curtain on climate-change politics and discuss how quality science reporting can play a role in helping Australia reach its emission targets.

This special episode of the Contact magazine podcast has been made in celebration of 100 years of journalism at UQ.

Listen to the podcast

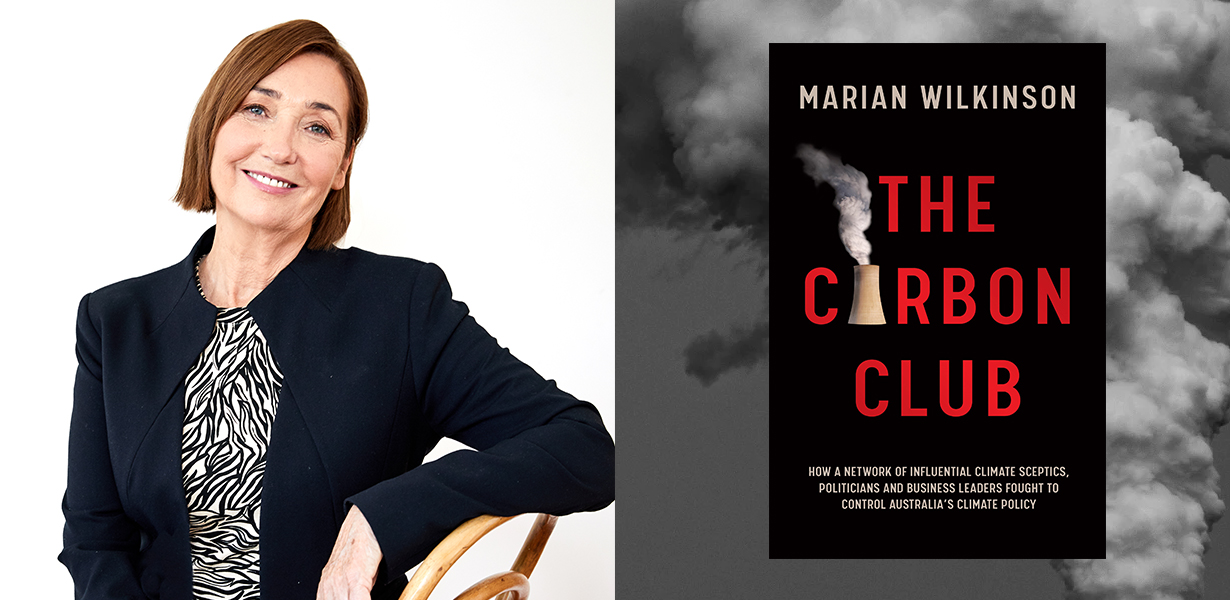

About Marian Wilkinson

Marian Wilkinson is a multi-award winning journalist with a career that has spanned radio, television and print.

She has covered politics, national security, refugee issues and climate change as well as serving as a foreign correspondent in Washington DC for The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age. She was a Deputy Editor of the Sydney Morning Herald, Executive Producer of the ABC’s Four Corners program and a senior reporter with Four Corners.

As Environment Editor for the Sydney Morning Herald she reported on the rapid melt of Arctic sea ice for a joint Four Corners-Sydney Morning Herald production which won a Walkley Award for journalism and the Australian Museum's Eureka prize for environmental journalism. In 2018 she was inducted into the Australian Media Hall of Fame.

Her latest book, The Carbon Club, investigates Australia’s fraught climate change policy and the network of players who derailed it.

To learn more about 100 Years of Journalism at UQ celebrations, visit the UQ School of Communication and Arts.

If you want more expert commentary and analysis on the topics that matter to you, visit Contact magazine.

This special episode was produced by Michael Jones and Rachel Westbury, and edited by Daniel Seed.

This year marks 100 years since UQ first began offering journalism to students. To celebrate the milestone, Contact will be publishing regular features this year tackling the major issues facing the industry today, while celebrating the success of UQ’s journalism students, graduates and the School of Communication and Arts. Keep checking the Contact website throughout the year to view these stories.

Learn more about study opportunities at the UQ School of Communication and Arts.

Read the transcript

Tegan Taylor 00:05

From droughts to raging bushfires to devastating floods, Australia has seen an alarming increase in the severity of weather events in recent years. Despite this, many believe our nation's political leaders have failed to take real action against the threat of climate change. But why is this? And what role does science reporting play in this narrative? I'm Tegan Taylor, an ABC Health and Science journalist and a UQ graduate, and I'm honoured to be the guest host for this Contact Magazine podcast episode as we celebrate 100 years of journalism at UQ. Today, I'm joined by another UQ graduate and a multi award winning journalist, Marian Wilkinson. Marianne, here we are back at the beautiful University of Queensland.

Marian Wilkinson 00:55

And I'm delighted to be here and delighted to be here with you Tegan.

Tegan Taylor 01:00

Likewise, we're like mutual fan club right now. So Marian, you just published your new book. It's called The Carbon Club: How a network of influential climate sceptics, politicians and business leaders fought to control Australia's climate policy. Tell us about this book and what has inspired you to write it.

Marian Wilkinson 01:18

I think I was inspired to write this by my terrible feelings of frustration in journalism covering this issue. It would drive me crazy. And part of the reason was, I think that I was going out doing stories about climate change and climate change policy on the one hand, and then on the other hand, this is when I was at Four Corners running around on the fall of this Prime Minister, the fall of that Prime Minister. And I was really frustrated that no one was putting this story together. How much of an influence all the backroom politics, about climate change, about resisting climate change policy, how much that was actually having an influence on tearing down Ministers, Prime Ministers, public servants, I could see it. But I think I needed this book to pull it all together. And so that's what I tried to do, to write if you like, a dramatic nonfiction narrative about those events.

Tegan Taylor 02:31

Because that that's a challenge with journalism, right? Like you've got all of these incremental stories, but the way that they're interrelated isn't always obvious.

Marian Wilkinson 02:39

That's right. And I would kind of think, 'Oh, God, why didn't the person in the press gallery you know, who's covering this mentioned x and y, and z?' But you realise that's not their job, they're on this incredibly fast daily turnaround where they've got to write all this stuff as it happens. I was sort of pulling back and, you know, and trying to see the big picture. And this is, as you said before, where the science reporting came into it, because my other big frustration was that both the journalists and the politicians were all having these ferocious debates at press conferences and elsewhere about climate policy and no one would talk about the science.

Tegan Taylor 03:26

So that's some of the logistical challenges. But what were some of the government challenges you faced when researching and then also eventually publishing the book?

Marian Wilkinson 03:34

It was, you know, in a funny way, it was easy and hard at the same time. What really surprised me was the generosity of both the climate scientists I spoke to, very generous with their time, with guiding me through research papers and things like that. Fantastic cooperation from the senior public servants who'd overseen these policies, saw every aspect of it, people like Martin Parkinson, who was head of the first climate change department, went on to be head of Treasury, and then head of PM&C, Prime Minister and Cabinet. Those people were really generous. Then there were the politicians, and some of them were amazingly helpful. But I had this overwhelming being with some of them where you felt like you were sitting in front of trauma victims, and they were so shattered by what they had gone through, trying to make climate policy happening. It was only then that I realised that so many of them had really taken this personally, the smashing of their careers over this issue. On the other side, you then had people, some people who were in senior positions in the current government who just absolutely cut me off. No, they didn't want to talk. Because the issue was just super sensitive. And then you had other ministers who'd ring and say, 'Look, I'll talk to you off the record, but don't don't quote me, you know how sensitive this issue is'. So yeah, it was a real mixed bag.

Tegan Taylor 05:24

So it's really politicised and really sensitive, obviously. Is that the same globally? Like how does Australia compare to other world leaders when it comes to climate policy and an emissions targets as well?

Marian Wilkinson 05:37

No, it's not the same globally. But what is interesting is there's a small group of countries, and Australia is one of the leading ones, Australia and the US, where this issue is super politicised. And there's a there's a very, as they would say, bleeding obvious reason for it. And that is because you have major vested interests tied up in the fossil fuel industry. Another, curiously, another country that gave a lot of credence to climate scepticism, scepticism about climate change, apart from Australia and America was Russia. And that's to a place where the gas industry, as you know, is hugely dominant in the government. So when you look at it that way, analytically, it's it's sort of pretty obvious. But I think the tragic thing for Australia, is that because those interests had an oversized influence on our politics. And that's what the book is about. I tried to explore those relationships, and really give you the nitty gritty on them, the nitty gritty of that influence exchange. I think the sad thing as we look back now in 2021, on this incredible period of friction in our country over climate change, all these basic policies that other countries in Europe have put in place, are not here. So while we've done some fantastic things, and there have been fantastic policies that managed to get through for a while, really critical architecture, not only around our emissions targets but also around adapting to the inevitable climate change we're going to get, have just not been put in place, or if it has been put in place was put in place by government that was replaced by another government that didn't agree with it, that therefore defunded it. So that's happened a lot.

Tegan Taylor 07:47

So that's here in Australia. And I think it's pretty well known that America is another one of those countries that has, it's a very political situation there when it comes to climate change. Do you think that Joe Biden's presidency will shift our climate action in the states and will influence Australia's response as well?

Marian Wilkinson 08:06

I think it's already greatly influencing Australian policy. And there is a huge thing about the US position. When the US shifts, the world shifts. And I think the me that- I saw that up close and personal when I covered the Copenhagen climate conference, which ended up in not so much failure, but a tragic stalling of policy. And that was when China and the US essentially could not get their act together, could not get any serious agreement on climate change. Obama, President Obama determined he would get that agreement and his climate envoy, his Secretary of State at the time, John Kerry, really pushed hard on Paris, they did the deal with China. Paris did work, it did happen. Trump then goes and pulls out. Climate policy goes backwards; goes backwards as well in Australia, now Biden and his old friend John Kerry are back in charge of climate policy. And I think, you know, the way we've already seen our Prime Minister use those words, 'net zero by 2050', even though he's not committing yet, even though he's saying, preferably to me, that is Joe Biden.

Tegan Taylor 09:32

I don't know if it was just me. But in 2019, it really felt like the climate conversation was starting to come to a head after that horrific summer of bushfires. And then we had COVID. And the conversation shifted, and I can't tell if that's a good thing or a bad thing. Like did we lose the momentum because of COVID? Or is it inevitable that we're going to get to the right place eventually anyway?

Marian Wilkinson 09:54

I think we did seriously lose momentum. And it was funny because I was writing the last part of the book at this stage and I was documenting the way that while the Prime Minister Scott Morrison and the Emissions Reduction Minister Angus Taylor were really try to hang on to the old policies, Australia was moving around them. And some of the backbenchers in the Liberal Party were really putting pressure on Morrison and his senior ministers. But what happened was something really critical. In Europe, and in other countries, but specifically in places like Germany, and the Scandinavian countries, and in Europe overall, there was a big decision that that large pot of money that needed to go into the economy, to help us through the pandemic would be tied to a transition in energy systems. And that began to happen really quickly in the UK, in Germany, and Norway, in Sweden, in all these other countries. It didn't happen in Australia. And that was a huge, I think, missed opportunity. And one of the reasons was, I think, one) the government decided that it would fall or rise on its policies towards the pandemic. That's certainly true, but that it could park climate change, because the public had, quite rightly, in a way to quite understandably, probably more accurately, I should say, the public didn't have the headspace. And that was, in a way sad, because at the same time, I was talking to people who'd been through the bushfires, or scientists who'd worked on the reef, who was still dealing with the destruction of 2019-2020. And they said they could just feel the momentum shift from them completely.

Tegan Taylor 12:10

So when there's- it's such a big complex issue, how do you prioritise which parts of it to talk about? Like, are there certain areas that need media coverage as a priority? Like I know you mentioned the reef. And I know that that's a real focus point for you.

Marian Wilkinson 12:24

One of the things I said to my publishers that I wanted to do was tell this very important political and policy narrative about, I think, why Australia blew its response to climate change. But I wanted to do that and include three chapters on the Great Barrier Reef that for me told the parallel story of the way we ignored our scientists, the way we ignored, if you like, the evidence before our eyes, and why we did it. And the crucial part of this is, why did we do it? Because I would interview reef scientists when I was working as a journalist. And they would say to me, why don't the politicians get it? Why don't they get it. But at the same time, I was watching the coal developments in Central Queensland, the gas developments in Central Queensland, seeing how much governments were building this into their budgets, building this into their economies. And in a sense, I felt like the scientists didn't have a chance. And now, of course, in as we got to 2020-2021 and we see the temperature rises in Australia, we see the marine heat waves coming through, we see the destruction on the reef, we begin to really see the consequences of climate change. And I wanted to tell that story in the book, that we are living with the decisions that we made, and I know it's a global issue. But it's also our decision making as well.

Tegan Taylor 14:22

Can we take a step back? I'd love to hear what got you passionate about science journalism in the start.

Marian Wilkinson 14:28

Well, you know, that's really interesting, because right the way through the 1980s and 1990s when, that tells you how old I am, when I was working as a journalist both for The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age and The Australian, and then Four Corners, I tended to be I suppose your classic hard-nosed investigative journalist. I- when I started out as a journalist actually at UQ at 4ZZZ at the student radio station writing for Semper Floreat, the student newspaper. I wanted to, you know, break open the Bjelke-Peterson government, you know, my heroes were Woodward and Bernstein. And I guess I was very dedicated to that path for a long time, until I just finished covering the Bush administration, the George Bush Jr. Administration and the Iraq war from Washington for The Herald and The Age, and I was finishing up and I was absolutely mentally, I think, exhausted by those politics of war, and terrorism and all that. And a friend of mine said, Look, you've got a few months off, I really want to do this documentary about climate change. I knew not much, not much. I knew a bit as an informed journalist, but it wasn't a priority of mine. He sent me Tim Flannery's book The Weather Makers and I began reading in the area. And because I was in Washington, my colleagues said to me, why don't you go and interview all these people who are involved in policy in Washington. And as I did that, I saw it opened up this huge world for me about the contested science over climate change. And it was at the time when the big oil companies like Exxon and the big coal companies like Peabody, were putting huge amounts of money into climate sceptic science in America. And that got me interested.

Tegan Taylor 16:41

But then you're bringing that that long, excellent grounding as a hard news reporter to that really contested political thing, like how do you then- or what skills would you have to draw on to remain impartial and to have that journalistic integrity when you were reporting on climate science?

Marian Wilkinson 16:58

Well, it was strange, because that documentary I mentioned to you never got made. And ironically, the reason it didn't get made was the English producers and funders of the documentary said to us, hey, this guy called Kevin Rudd, has just got the Leader of the Opposition's position he's gonna run on climate change. And Malcolm Turnbull has gone in as Environment Minister, hey this debate's over. This debate is over, we're pulling the money. Anyway, so then I went back into journalism. But I asked the Herald, The Sydney Morning Herald, the paper I was going back to work for, would you- the job I really want to do is cover this issue. And going back into daily journalism for me, which I, you know, in the past I'd done investigative journalism or foreign policy journalism, I was going into very much daily journalism. And that was a thing where you had to deal with ministers, you had to deal with bureaucrats, you had to deal with what is. And that put me straight back on the road of, Okay, I've got to talk to everyone. And therefore, you've got to represent everyone.

Tegan Taylor 18:13

Which is, of course, what's laid the groundwork now for this book, which is amazing. But back at the beginning, like I wonder when you left school, so you left school in Year 10. Did you imagine this is where you'd end up? Like, what's your journey been to get to this point?

Marian Wilkinson 18:27

I did not believe I would end up here at all. You're right. I left school at the end of Year 10. A very kind of, if you like disillusioned kid from housing commission state, but with parents who absolutely treasured the idea of education, and their disappointment in me at the time, I can tell you is quite profound. But my father was really fantastic. He said, okay, you want to leave school at Year 10. Pay rent, get a job, see how you like it. Hated it. Went back to Corinda State High here in Brisbane, had two brilliant teachers. And people always say this, had the most wonderful history teacher you could imagine working in a quite a working class state school in Brisbane. And he just encouraged me and encouraged me, encourage me so much that I ended up winning the Queensland University AIF's prize for history in the senior exam from school. So and that I can say was not me that well, maybe a little bit me, it was this teacher and got a scholarship to Queensland University and basically found myself.

Tegan Taylor 19:52

So this is this year's 100 years since UQ first began offering journalism to students is that what you studied when you were at uni?

Marian Wilkinson 20:00

Ironically not. I actually studied English and History, my passions, a little bit of economics, but mainly my passions of history and English but I did immerse myself in the student paper with students from the journalism school and got to know them and loved Semper Floreat. Just found that I loved writing and exploring things, and then working on the student radio station, the same thing and then started just ringing national papers like Nation Review, saying, Would you take a piece from us, you know, me and another student? And amazingly, they said, Yes. And managed to get my first libel, which I think I was about 20. But luckily, it didn't go anywhere. But yes, and I was absolutely hooked. And I, and I guess I took on board all those values at the time, you know, afflict the comfortable, comfort the afflicted, you've got a duty. And I guess I, I've always seen that journalism as a duty to the public.

Tegan Taylor 21:18

Journalism as a field has changed a lot since you or I were at uni here, and certainly in the last 100 years, but is there anything that you would say to a young would-be journo about how to make the most out of those early years?

Marian Wilkinson 21:33

Have some courage. Follow your instincts. And I know it's completely trite, but work hard. You know, I think I had some wonderful mentors when I went into journalism. You know, Paul Kelly, Brian Toohey and Summers, these- David Marr, the sort of greats of the industry. And one thing I learned really quickly from then is that they wanted to do journalism differently. They didn't want to go on the word of the minister or the press release from the corporation. They wanted to dig behind it. To do that they put in the work. They read things, they read the policy documents, they talked to people who worked in the area, they became informed. And I think, and you would know this Tegan and because I know you and Norman do this all the time, but you really dig in to the subject you're doing. And I think that's the only way that you can do serious journalism.

Tegan Taylor 22:41

Well, that kind of brings us to the science side of your passion, like what's the role of the university in educating and promoting science and environmental journalism as a specialty area?

Marian Wilkinson 22:52

I think it's absolutely crucial. Through some of the most heated days that I covered climate change policy during the Rudd years, the Gillard years, the Turnbull years, when the debate over climate change were utterly vicious and completely, I think, distorted. The fact that I could go to great scientists at University of Queensland, like of course, the wonderful Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, to people at JCU, James Cook University, to scientists at Melbourne University and ANU, they set you back on this path of what really matters. And, to me, one of the saddest things that I had to cover in the book was the way all those really important scientists went through hell in those years. These are scientists who, you know, we don't think enough of them really. But they're the ones who were, you know, the lead authors for the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), Australian scientists have just been so so important in helping to alert the world to not only alert the world to climate change, but what we should be doing about it. But as a reporter, during all those years, they became almost like a safety net for me intellectually, that I could go there, I could go to them, go back over the science, be reassured that you know, you weren't biased this way or the other. You weren't crazy. You weren't going over the top,

Tegan Taylor 24:40

Oh these voices and more are obviously, underpinning your book. So Marian, where can people get their hands on The Carbon Club?

Marian Wilkinson 24:47

Well, at every good bookshop, but certainly if you go through Allen & Unwin, the lovely publishers, they will also get you a copy I am sure, and I'm very fortunate to be doing some speaking events. I really don't like promoting my own work. But I do say in this case, this is a book worth reading, because so many young people, including my stepchildren, say to me, 'but why did your generation let this happen?' And I say to them, there are a lot of people in my generation trying to do things. And there, as well as the people who are stopping this, the other side of the book is all the people who were trying to write the science, publish the science, publish the policy that would work. So I think it's a it's a book, so many people have said, I've read the book, and I was so angry at the end. But other people, I think, do also get that there's so much hope in the book, because you realise there were all these people doing all this work, we can now draw on.

Tegan Taylor 26:08

And there's still hope. Marian Wilkinson, thank you so much for joining us today.

Marian Wilkinson 26:11

Thanks, Tegan. It was an absolute pleasure.

Contact magazine editor, Michael Jones 26:20

That brings us to the end of this Contact Magazine podcast episode. We would like to thank our esteemed UQ graduates and journalists Marian Wilkinson and Tegan Taylor for this insightful interview. To learn more about 100 years of journalism at UQ celebrations, visit the UQ School of Communication and Arts website. If you want more expert commentary and analysis on the topics that matter to you, make sure you visit the Contact Magazine website at alumni.uq.edu.au/contact-magazine. Thanks for listening.